Make it or break it for carbon trading?

Countries all over the world are adopting carbon trading. Will the emerging carbon markets manage to steer clear of the many pitfalls involved in emissions trading – or are we headed for a carbon-market backlash?

This was among the key questions raised when the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI) hosted a conference on emissions trading schemes (ETS) in Oslo, Wednesday 10 May.

Red China goes green

Conference speakers provided insights from various carbon markets across the globe, with  special attention to China’s upcoming ETS. Set for launch sometime this year, it will be the world’s largest national carbon market by far.

special attention to China’s upcoming ETS. Set for launch sometime this year, it will be the world’s largest national carbon market by far.

For many, it may sound paradoxical that the centrally-governed, ‘Communist state’ of China has decided to embrace a decentralized, market-based instrument like emissions trading. And many are asking whether the Chinese ETS will be able to deliver, given the vastness of China, the huge economic differences between its various provinces, and not least the country’s problems concerning the lack of transparency and reliable environmental data.

China will definitely be the “make it or break it” for ETS globally’, says emissions trading expert, Stig Schjølset, who was among the key speakers at the conference. He has worked for many years in the carbon-market analyst firm Point Carbon, and is currently serving as special advisor to the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment.

‘It will be crucial for China to make ETS work as a greenhouse gas mitigating policy tool, not least because of the amount of political prestige invested in the project’, explains FNI Senior Researcher Gørild M. Heggelund, an expert on Chinese climate policies. ‘The Chinese President himself announced that the ETS is happening and that the market will be launched in 2017. A great deal of effort has been put into this, politically and technically, so the stakes are high’, she adds.

Going global?

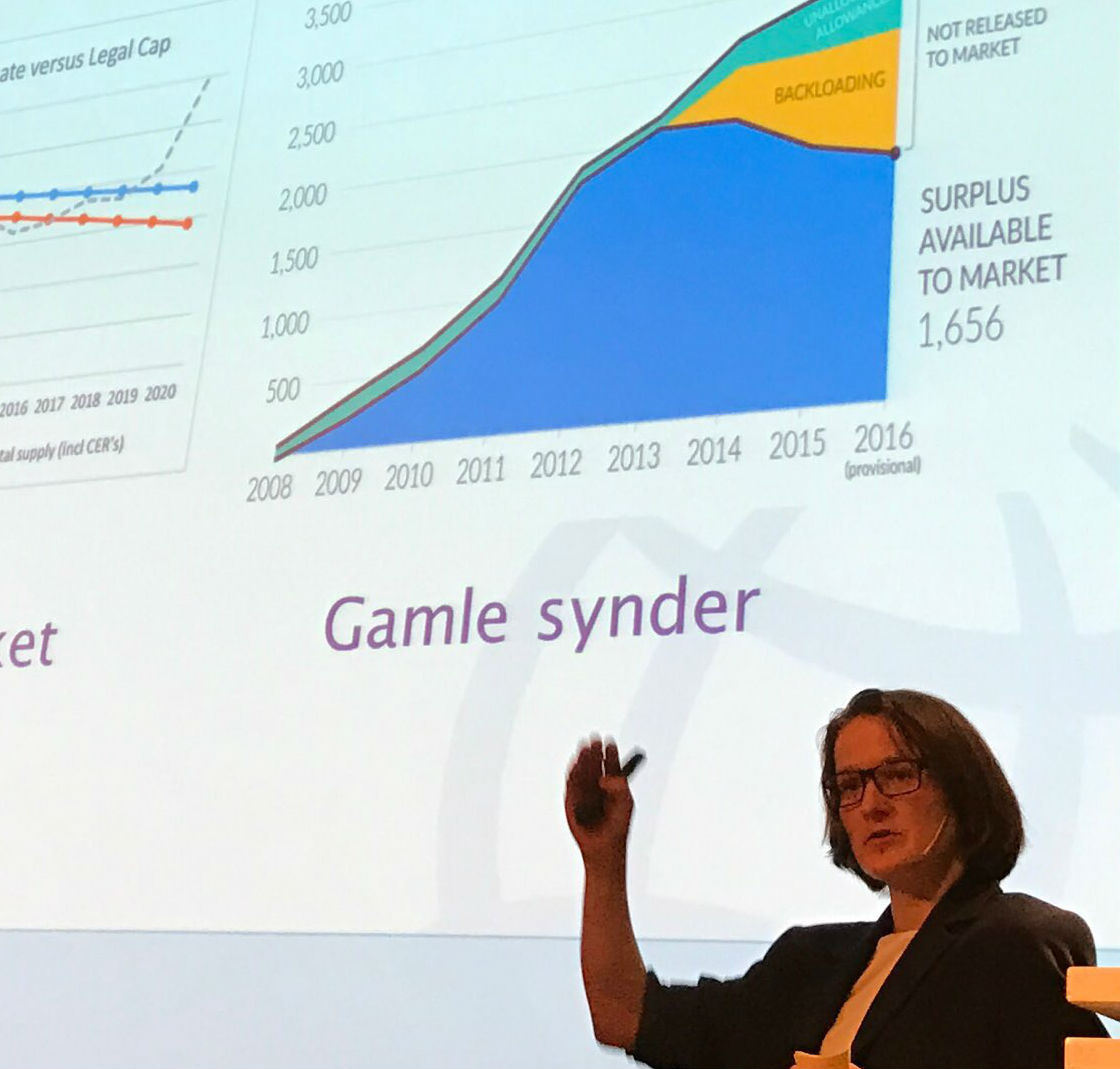

Guri Bang, Research Director at CICERO Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research, gave a presentation on the history and the current status of the Californian ETS, locating the case within a broader ‘US post-Trump’ context as well. FNI Researcher Torbjørg Jevnaker provided a recap of the many hurdles faced by the EU ETS and how the EU is currently trying to tighten and reform its troubled carbon market.

Guri Bang, Research Director at CICERO Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research, gave a presentation on the history and the current status of the Californian ETS, locating the case within a broader ‘US post-Trump’ context as well. FNI Researcher Torbjørg Jevnaker provided a recap of the many hurdles faced by the EU ETS and how the EU is currently trying to tighten and reform its troubled carbon market.

Speakers at the conference also examined other parts of the ETS world, including Kazakhstan, South Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, Australia and New Zealand. The idea of emissions trading and its practical relevance as a climate policy tool certainly seem to be gaining ground, at least geographically.

The risk of fiasco

With this global ‘diffusion’ of ETS, could we be headed for a larger, more interlinked and thus more efficient and better-functioning global carbon market? Or might some of the countries now launching or planning to launch emissions trading lack the necessary expertise, bureaucracy and state capacity? If so, will more ETS diffusion be followed by more ETS ‘fiascos’?

There is certainly a risk of backlash’, says Research Professor Jørgen Wettestad, who has headed the FNI’s ETS Diffusion Research Project.

‘Our project has clearly documented the spread of emissions trading as a climate policy tool. More and more countries are pledging to include emissions trading as part of their political portfolio. While the spread of emissions trading could be seen as a positive development, at least on paper, moving too fast could also backfire. We see this in the case of Kazakhstan, which shows that making ETS work requires much more than just the political will to do so.’

‘Our project has clearly documented the spread of emissions trading as a climate policy tool. More and more countries are pledging to include emissions trading as part of their political portfolio. While the spread of emissions trading could be seen as a positive development, at least on paper, moving too fast could also backfire. We see this in the case of Kazakhstan, which shows that making ETS work requires much more than just the political will to do so.’

Too little, too late?

Despite the many initiatives underway in various countries and regions, Stig Schjølset sees no sign of a more interconnected, global ETS emerging:

‘ Quite the contrary – emissions trading is increasingly becoming an “introverted” policy instrument. Symptomatically the EU will be closing its system from 2021 on. We have never been further from the goal of a global, interconnected carbon market. The UN-based credits which provided an indirect link between different systems are now withering away, and emissions trading serves primarily as a national policy tool.’

Quite the contrary – emissions trading is increasingly becoming an “introverted” policy instrument. Symptomatically the EU will be closing its system from 2021 on. We have never been further from the goal of a global, interconnected carbon market. The UN-based credits which provided an indirect link between different systems are now withering away, and emissions trading serves primarily as a national policy tool.’

Speaking at the conference, Schjølset also argued that, in terms of actual, short-term results, emissions trading so far has very little to show:

We are currently seeing a technological revolution, not least in the transport sector. This is not thanks to emissions trading – it is the result of other policy instruments. And it is happening really fast. So, yes, we might be able to make emissions trading work better in the future, but by then, ETS could come too late to the party – it might then be too late for ETS to make much of a difference.’

Not just 'one party'

Jørgen Wettestad pointed out that many emissions trading systems are relatively young and that their functioning will be a main topic of research also in the years ahead. Moreover, since different carbon trading systems play different roles in the policy mixes globally, there is not one low-carbon transition party to attend, but many.

To view the whole programme as well as the power-point presentations from the 10 May conference, please click on the links in the right-hand column of this page.

For more news on climate policy research at FNI and invitations to upcoming FNI events, subscribe to our newsletter here.